Wildlife Corridors:

A Key Focus for the Mountain

One night in 2009, a black bear was spotted by five different people near Adobe Creek in Petaluma. After being chased by a helicopter, the bear followed that creek back up and over Sonoma Mountain to return to Napa County from whence he or she had probably started.

It is likely that this adventurous ursine was using the Sonoma Valley Wildlife Corridor to travel from Napa County through the Sonoma Valley and up and over Sonoma Mountain.

This bear didn’t just drop into Petaluma — he or she had been able to travel a long distance, safely and mostly unseen, through existing land and creek corridors. Such corridors are essential for wildlife passage — not just for large carnivores, like bear and mountain lion, but for the many smaller critters as well, like raccoon, fox and bobcat.

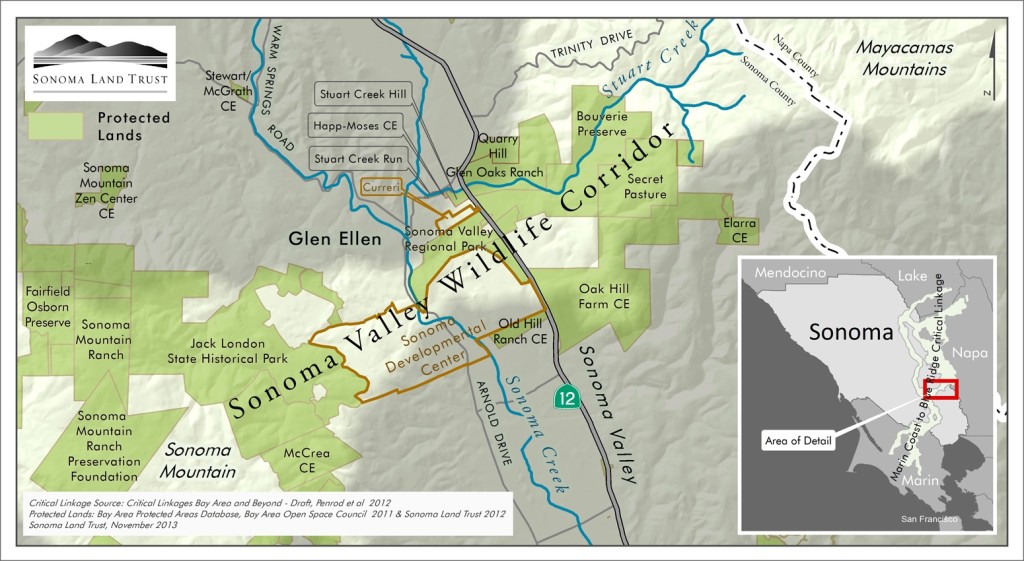

Sonoma Land Trust has embarked on a multi-year project to keep open a narrow pinch point in the high-priority Sonoma Valley Wildlife Corridor that is at serious risk of closing up. Five miles long and only three-quarters of a mile wide at its narrowest point—the “pinch point”—the Sonoma Valley Wildlife Corridor stretches from Sonoma Mountain, across Sonoma Creek and the valley floor, and east to the top of the Mayacamas range. It is located within the “Marin Coast to Blue Ridge Critical Linkage” identified in the Bay Area Critical Linkages Project and Conservation Lands Network, both projects of the Bay Area Open Space Council.

Because of the work of SLT, SMP, and others over the years, more than 8,000 acres of the corridor are already protected as natural land. It is the unprotected land at the heart of the wildlife corridor on which efforts are now focused.

Ensuring that wildlife can move safely through the landscape so their populations can persist in the face of development and climate change projections is the goal of this large-scale project. Acquiring new properties is only one way of accomplishing this.

“We can’t afford to buy the entire corridor, nor would we want to because collaborating with private landowners is a very effective conservation strategy,” says Wendy Eliot, Sonoma Land Trust’s conservation director. “So we are using a variety of land protection tools to protect and enhance the corridor’s permeability, such as deed restrictions and new types of conservation easements and neighbor agreements — along with purchasing at-risk parcels.” SLT staff is developing model conservation easement language, focused on “wildlife freedom of movement” that will be used by many conservation groups working to secure wildlife corridors.

To validate the theory that this area is operating as a functional wildlife corridor, SLT has placed wildlife cameras on Sonoma Mountain and up and down the valley to collect data on the animals who live there. Cameras have captured mountain lion, fox, dueling bucks, opossum, bobcat, skunk, coyote, turkey vultures, jackrabbits, squirrels, and more.

The role of SDC wildlands is crucial to preservation of the wildlife corridor. The SDC Coalition, of which SMP and SLT are a part, aims to create a scenario in which the clients’ needs are served while providing urgent environmental protections — for the wildlife corridor, watershed preservation and public access. Successful protection of the undeveloped portions of the SDC would directly link more than 9,000 acres of protected land and help ensure the continued movement of wildlife across the Sonoma Valley and beyond. There are no do-overs once land is developed.

Simple things landowners can do to improve wildlife movement:

• Remove unnecessary fencing

• Modify fencing for wildlife passage

• Turn off lights at night

• Don’t leave pets (or pet food) outside at night

• Reduce nighttime noise

• Eliminate or minimize pesticide and herbicide use

• Modify vegetation management: Protect your home from wildfire, but leave enough cover for wildlife.

Map, infrared camera photo, and information courtesy of Sonoma Land Trust