Camp Via transferred to Jack London State Historic Park

By Tracy Salcedo

Originally published in Kenwood Press, June 15th, 2024.

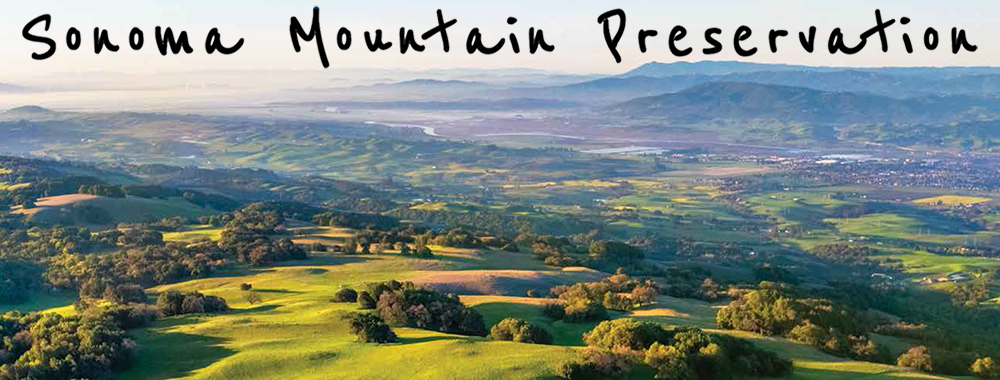

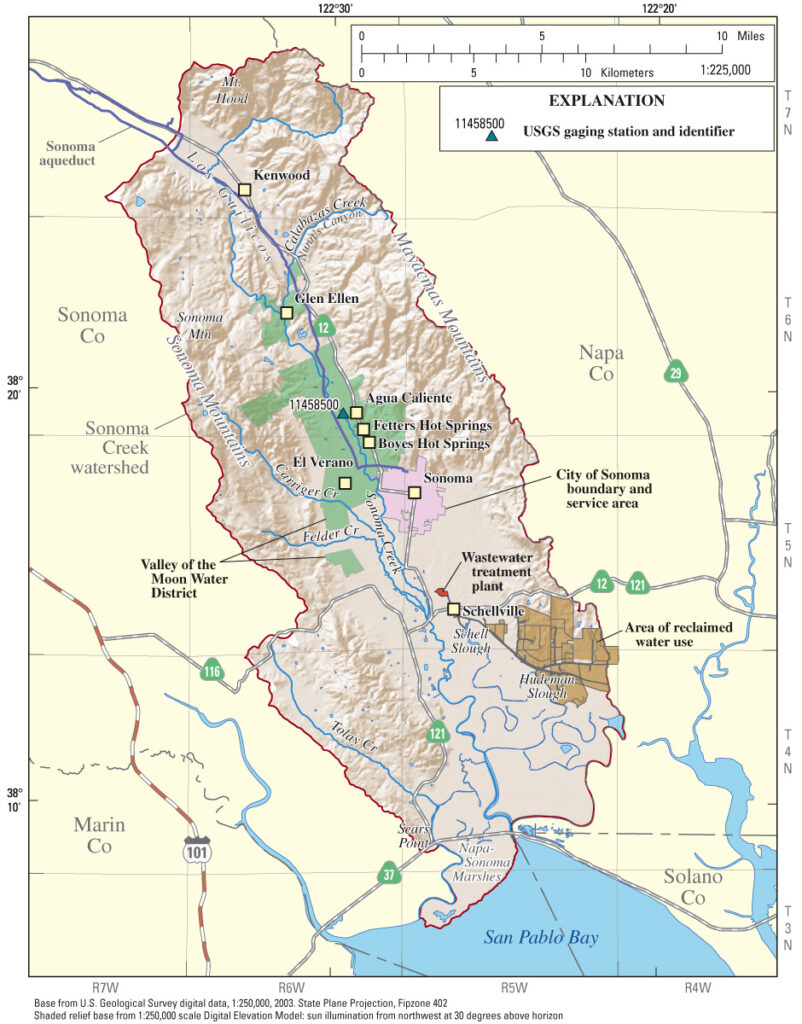

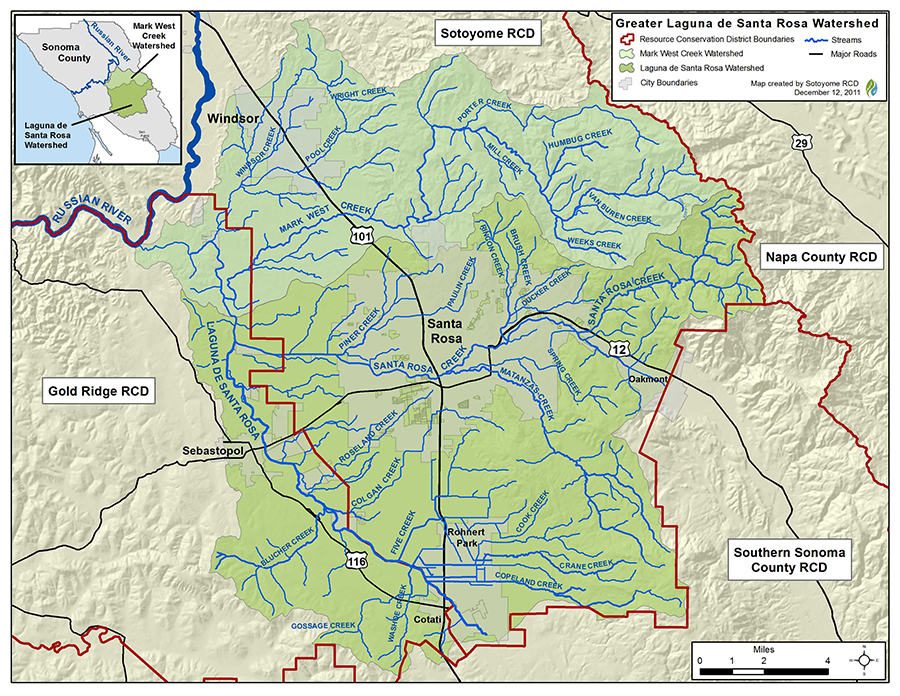

Camp Via, tucked next to Jack London State Historic Park’s historic orchard on the forested east-facing slopes of Sonoma Mountain, has been folded into Sonoma Valley’s portfolio of public parkland.

The 11.4-acre camp is the “final piece” of former Sonoma Developmental Center (SDC) open space to be transferred to California State Parks, according to a June 3 press announcement. “This move underscores the commitment to fulfill the state’s objectives and obligations regarding the SDC Specific Plan, prioritizing the conservation of open space and natural resources,” the release states.

A total of 661 acres has been added to the park since January, encompassing the old camp, an informal trail system linking the historic orchard (also once part of the SDC) to the 180-acre campus, the Sonoma Valley Wildlife Corridor, and wildlands surrounding Lake Suttonfield. Jack London State Historic Park (SHP) now stretches from near the top of Sonoma Mountain to Highway 12 on the Sonoma Valley floor.

The transfer was lauded by state Senators Bill Dodd and Mike McGuire and state Assemblymember Damon Connelly, as well as State Parks director Armando Quintero and Wade Crowfoot, Secretary of California’s Natural Resources Agency.

“The transfer of Camp Via, a historic retreat and campground in the heart of the SDC, is another milestone in this transformational project,” Sen. McGuire said in the release. “We’re grateful for the ongoing partnership with Senator Bill Dodd, the community of Sonoma Valley, and State Parks to get this important piece of the SDC transformation project in place and open for public access.”

“I’m happy to see the state delivering on its promise to protect this beautiful land and make sure it’s available to the public for hiking and outdoor recreation,” Sen. Dodd said. “Increasing access to open space is critical, and I’m confident State Parks, working with the local community, will steward and protect this incredible property for generations to come.”

Matt Leffert, executive director of the nonprofit Jack London Park Partners, expressed excitement at the possibilities Camp Via offers given its location at the “gateway of the historic orchard” and proximity to hiking trails on the park’s southern boundary.

“We will be working with state parks and the community to determine the best use of the site, and in the meantime, we will be providing staff and volunteer support to begin clean up and vegetation management,” said Leffert. “We are super excited to be partnering with State Parks to improve the area and explore opportunities to offer new amenities to park visitors.”

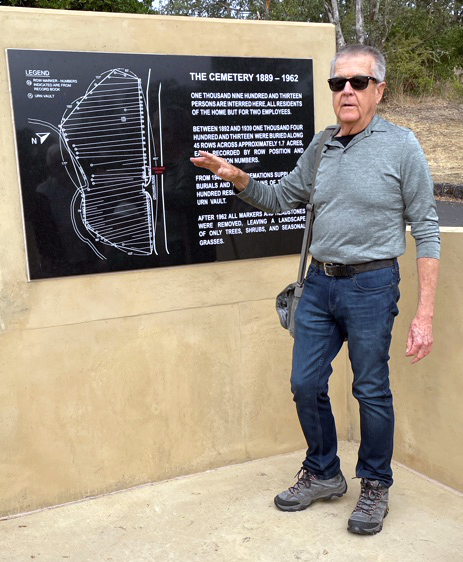

A little history

Thousands of residents of the SDC, a long-standing institution for the developmentally disabled that closed in 2018, enjoyed the seclusion and outdoor wellness provided by Camp Via over decades. Opened in 1963, when the SDC was known as Sonoma State Hospital, the Volunteers for Institutional Aid (VIA) provided the resources and financial support to establish the camp on land formerly associated with the hospital’s orchard operations. According to one newspaper account, in 1969 as many as 1,400 disabled children spent a night or two at Camp Via over the course of the summer months.

An article from the Aug. 1, 1965 edition of the Press Democrat describes how disabled children from the hospital, whose worlds seldom opened beyond the “walls of their wards,” were able to enjoy all the pleasures of traditional summer camp, with the help of volunteers and staff, at Camp Via. Arts and crafts, roasting marshmallows, horseback riding, cooking meals on hand-built camp stoves, dancing, archery, team sports, water play, and “traditional campfire ceremonies” were all on the docket.

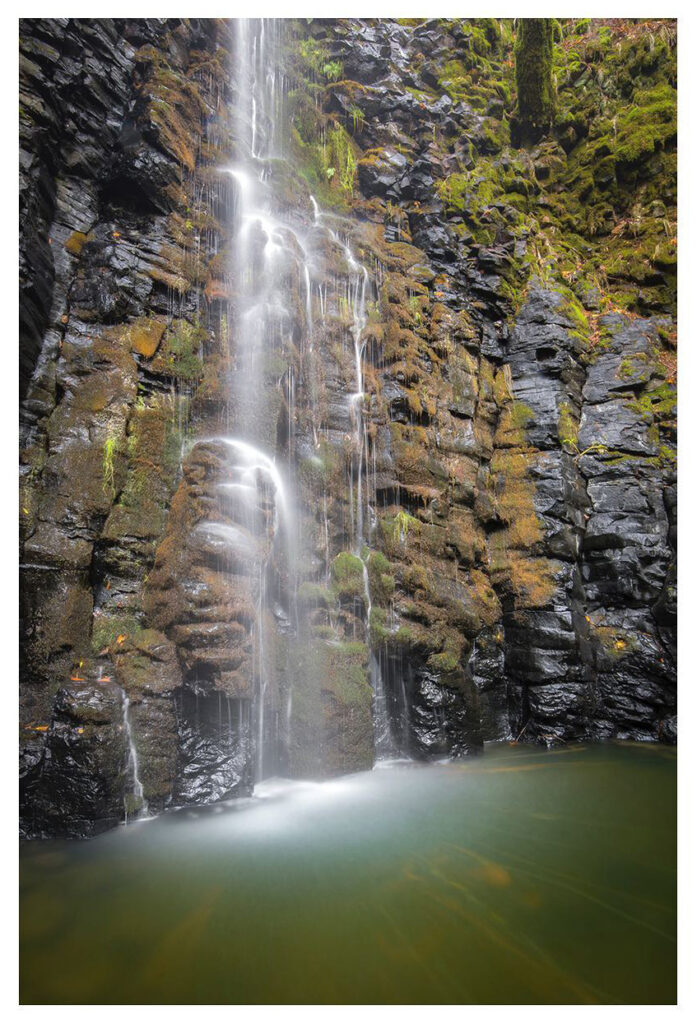

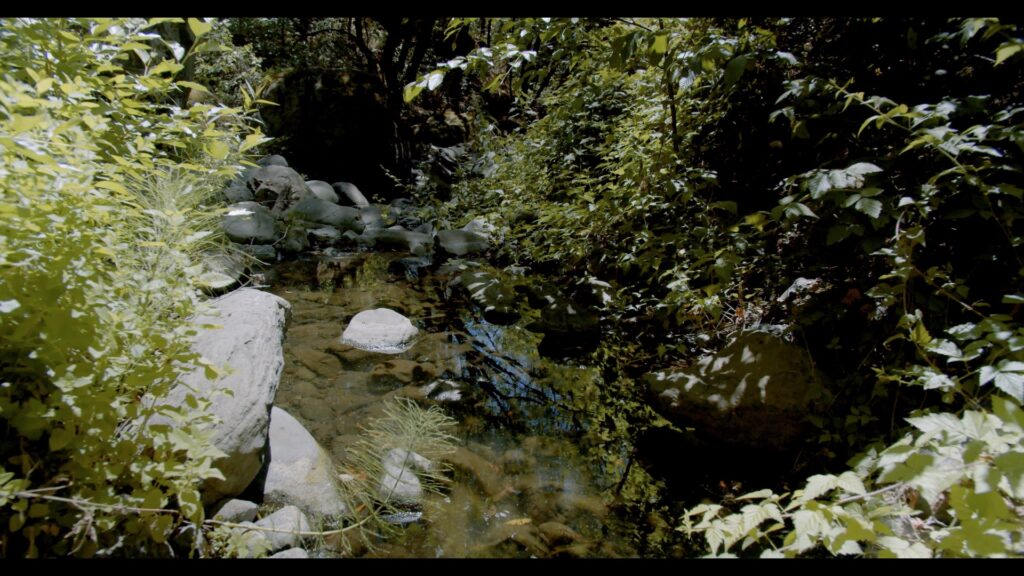

So too was work, according to the article. The nightly campfire site was “situated in a beautiful redwood grove, verdant with ferns,” but to get there campers had to negotiate steep hillsides and a creek crossing. To make the evening sojourn easier, campers carved stairsteps with spades and shovels, and “painstakingly constructed a rustic bridge across the creek bed,” all under the supervision of camp counselors.

Though reaching Camp Via involved a “teeth-rattling” ride up the now paved Orchard Road, “the facility is located in a beauty spot,” the reporter writes, “…its scenic impact [emphasized] by its location on Sonoma Mountain, about 1,100 feet above the Valley floor and hospital.”

The beauty spot remains, but the camp has since fallen into profound disrepair, its ramshackle cabins dismantled after being damaged by falling trees and tree limbs, as well as neglect.

Plans for the future

While details about how Camp Via might be used moving forward were not available at press time, a new website provides insights into how State Parks plans to integrate the new SDC parkland into the existing park, as well as changes park users can expect.

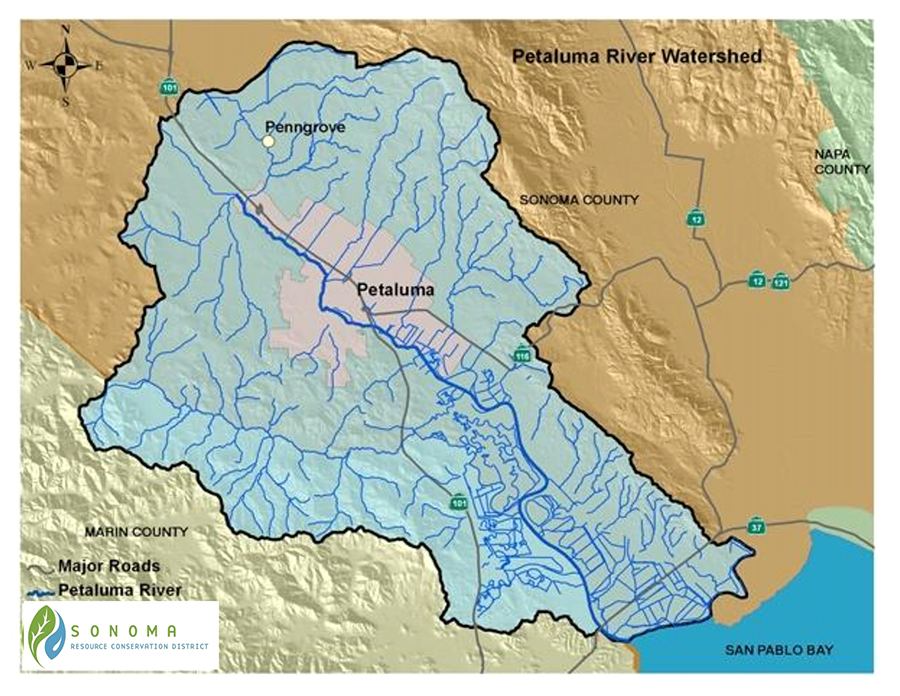

The most significant of those changes, at least for local residents who frequent the SDC trail system with their pooches, is the restriction of leashed dogs to paved roads. Swimming in both Lake Suttonfield and Fern Lake is prohibited; both reservoirs “remain with the local water district [and provide] valued drinking sources for residents and future development.” Removal of dead or downed wood is also prohibited, as is use of firearms. Restrictions on smoking and protections for other natural resources, such as wildlife and wildflowers, are spelled out.

The website also states that “… CalFire will receive a portion of the southeast property for a future new facility.” This parcel, about 50 acres, is bordered by Highway 12 on the east; a map shows the configuration of the carve-out, as well as trails, trailheads, and permitted uses on the land.

An outline for a five-phase planning process for the new open space, which will include a general plan amendment for Jack London State Historic Park, is posted on the site. The general plan amendment will cover trail maintenance, interpretive programming, public access (trailheads), and vegetation and wildfire management, as well as require tribal consultation, public input, “community and stakeholder engagement,” and inventories of resources.

For more information and to sign up for email updates, visit parks.ca.gov/SDCOpenSpace, write bayareadistrictoffice@parks.ca.gov, or call (707) 769-5652.