*Originally published in Kenwood Press

I was walking so slowly I felt tipsy.

But that was the point. Not the tipsy part, the slow part. As part of my California Naturalist training, I was being introduced to forest bathing, which invites you to walk so slowly that you notice things you might otherwise whiz past. Embracing the invitation I wobbled down the nature trail, drunk on spiderwebs, birdcall, and moss.

I’ve always considered myself a slow walker, but it turns out I’m not. I’m a stop-and-go walker. Writing hiking guides requires moving along a trail in fits and starts, pausing at junctions and overlooks to take notes, then whizzing to the next waypoint. I stop to make notes because otherwise … well, tipsy.

So yes, I’m slow, but only because it takes me a long time to write notes. Stop-and-go walking is a job. Slow walking is a gift.

Slow walking at Sugarloaf

The Cal Nat training I’ve just completed required reading and attending lectures by experts in the fields of geology, hydrology, biology, and more. It also involved slow walks to places in Sugarloaf Ridge State Park where that geology, hydrology, biology, and more could be witnessed in the wild. The program has long been a goal of mine — I know little bits about the state’s natural wonders and this was my chance to take a deeper dive.

On a hillock underlain by serpentine, my fellow aspiring naturalists and I spread across the slope and moved slowly, looking for new things to identify using the iNaturalist program: insects, snakes (or not), lichens, leather oak. On top we gathered in the broiling sun and talked about how plate tectonics are like pizza, and how fire is both good and bad. Then we head down to the creek to forest bathe.

I’ll admit to approaching forest bathing with skepticism. If bathing equals immersion, my entire career as a professional walker in the woods has been an extended soak. But I was missing something important: intention. Forest bathing is not simple immersion; it too is a deep dive.

We began by a mandala — a circle of leaves, flowers, acorns, and stones — where I offered gratitude to my family. We sipped tea. Then we walked slowly up the trail carrying our gratitude and intentions to pay attention, and then down to the creek, where we were invited to hold an open hand just above the water to feel the tension there.

Unfortunately, I missed out on this experience. I have no depth perception — never have — so I plunged my flat hand straight into the water, truly bathing. I stifled laughter because I knew the others were getting this thing right and I didn’t want to distract them. Acting natural, I selected a stone from the creek bed like that’s what I’d intended, and cradled it my palm as we gathered round to share our experiences. I made myself a promise to feel the surface tension of water some other time, in private.

On another day in Sugarloaf, near the headwaters of Sonoma Creek, we settled onto a bridge and pulled out our notebooks. While we wrote and drew in our nature journals, the weather began a slow turn, blowing open a storm door. The class carried on up the trail but I had an appointment; this was my turnaround.

I was packing my bag when the yogis arrived. “Join us,” the leader invited, and there on the bridge she anointed my wrists with a scent that blossomed on my skin like the smell of home: bay, wild rose, sage. I stretched with the yogis for a short time, breathing into the lake of healing I carry in my core. I only had time, though, to stretch half my body before I had to move on — and I know enough about yoga to know I was out of balance. But these days I feel chronically out of balance so I slow-walked back to my car, careful not to be tipsy when I turned my face to the gathering wind.

Slow walking on Sonoma Mountain

On the other side of the valley on another day, a certified Cal Naturalist led a crew of curious hikers around the Sonoma Developmental Center (SDC) campus on a guided walk. We were exploring the cultivated forest that thrives among the decaying buildings: cypresses, redwoods, catalpas, oaks, magnolias thick with fruit. It’s a mast year for magnolias and some of the oaks, and they have produced in abundance for reasons humans have yet to suss out completely.

I was acting as sweep. What’s a sweep, you ask? It’s the person at the back of the pack of a guided hike who makes sure no one gets left behind. It turns out some folks walk slower than others, and some folks just forget to walk at all, diverted by their devices or a friend they meet along the trail. We walked slowly not just because of all there was to see, but also for the stories; we were a group who knew the SDC’s history well, and who were curious, and who gathered berries to munch and pebbles to toss from the bridge as we meandered.

Back at the SDC on another day, this time sweeping a literary bird walk in the open space above the campus, I reconnoitered with the leader under a dripping cypress. Our announcement for this hike noted heavy rain would cancel, but the six of us who’d gathered for the hike decided heavy rain be damned.

Our guide began with a poem and advice: We must walk quietly if we want to spot birds. In the same way telling someone that a person is blind makes that someone yell at the blind person, walking quietly also means walking slowly. We saw a whole mess of birds. A flock of bushtits called out warnings — “Head’s up!”, “Take cover!” — when a Cooper’s hawk flew overhead, because the big bird eats the little birds. Lesser goldfinches, a Hutton’s vireo, ruby-crowned kinglets, and dozens more braved the weather. The wet adobe soil became snot-slick and stuck to our boots, forcing us to walk even more slowly. We paused in downpours to read poems and peer into bushes. By the time we reached Fern Lake, we were drenched.

But no matter. On the way down we were all a little tipsy, intoxicated by mist, birdcall, and moss, the gifts of slow walking.

Connect with SMP

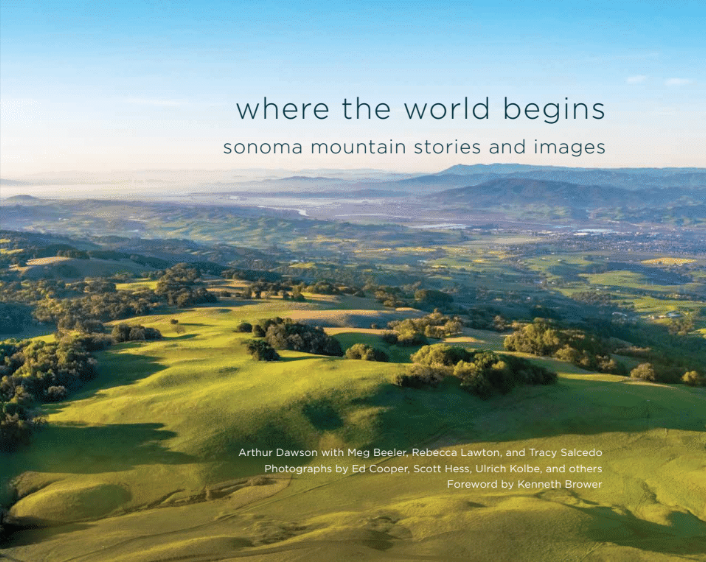

Sonoma Mountain – The Book!

Where the World Begins: Sonoma Mountain Stories and Images draws you into our inspiring natural treasure at the heart of southern Sonoma County. Local Bestseller, IPPY Award 2020. Two purchasing choices below: