On March 10, Sonoma Mountain Preservation (SMP) joined about 250 community members to protest plans for intensive, out-of-scale redevelopment of the former Sonoma Developmental Center campus. SMP’s vice chair, Tracy Salcedo, was the keynote speaker and delivered a heartfelt and informative speech, posted below:

I want to start by acknowledging that we all stand on the ancestral lands of the Coast Miwok, Pomo, and Wappo peoples, who are still here and still tending this place. Your wisdom and spirit are my inspiration.

I’d like you all to look up and out to the west.

That’s Sonoma Mountain, part of a range that stretches north to Taylor Mountain, on the outskirts of Santa Rosa, and south to Cougar Mountain, near the Sonoma Baylands.

The Sonoma Mountain Range is the focus of Sonoma Mountain Preservation, or SMP. I’m SMP’s vice chair. We’ve been advocating for open space preservation and access on the mountain since 1993, in partnership with many others around the county.

It’s helpful to think about how important this mountain and range are to everyone who lives near it by thinking about its watersheds and viewsheds.

Sonoma Mountain is the backdrop for Sears Point, Petaluma, Cotati, Rohnert Park, Santa Rosa, Sonoma, and unincorporated villages throughout the Sonoma Valley and beyond.

Sonoma Mountain’s creeks feed the Petaluma River watershed, the Russian River watershed, and the Sonoma Creek watershed.

Sonoma Mountain is in us. Sonoma Mountain nurtures us.

Now, I’d like you to follow the western slopes of Sonoma Mountain down to Sonoma Creek, across Sonoma Valley Regional Park, across Lake Suttonfield, and up into the Mayacamas Range.

The mountain, and the land connected to it, are part of a wildlife corridor that stretches from the coast to Berryessa-Snow Mountain National Monument and beyond.

We humans aren’t the only ones who rely on this mountain for our health and well-being. So do bear and puma and salmon and newts and hawks and thrushes and snakes and raccoons.

So do oaks and manzanita and redwoods and bunchgrasses and mushrooms and fiddlenecks and lupines and poppies.

As many of you know, I’m a walker. In these days, I’ve been walking our newest state park lands with relief and gratitude. Together, we have set aside 650 acres of former SDC open space as a park.

A park.

That makes my heart sing.

But here’s the thing. We’ve got new parkland, but we’ve also got a development plan for this campus that presents a major threat to the viability and the promise of that park.

Consider the wildlife corridor.

As it stands, in this moment, the developer plans to erect a four-story resort hotel on a knoll within that corridor.

There would be demolition. There would be construction. Then this, which I can vouch for with recent experience, having just spent week in a resort hotel in San Francisco at the Public Lands Alliance conference.

The lights will be on all day and all night. People will come and go all day and all night. It will be a human corridor, not a wildlife corridor. A hotel in that place will put a crimp in a pinch point that is already delicate and tenuous.

Consider the impact on the open space surrounding the development.

One of the major themes of the Public Lands Alliance conference was the incredible growth in the number of people visiting parks in the last few years.

This has turned out to be a double-edged sword. To avoid overuse — to keep from loving the places to death — people need more open space. Acres and acres of open space.

This need has been studied and proven and is universal.

The 100 acres of open space that have been removed from redevelopment plans matter.

Now, consider the community voice.

We were promised a community-driven plan for this place. In that community-driven plan, preservation of open space was prioritized.

The plan presented by the developer, and the recent transfer of 50 acres of open space for construction of a separate CalFire campus, diminishes that open space not only in the number of acres, but also the density and placement of development.

It doesn’t matter what local community you associate with. You could be labeled with any number of derogatory or local or progressive agendas.

But what we see here, in these newly revealed plans for the SDC, is not community-driven.

What we see here does not prioritize what the community knows is important.

What we see here is the imposition of narrow agendas conjured by bureaucrats that benefit a developer, not the community.

I am a storyteller. I’ve been telling the story of the SDC, and its redevelopment, in various venues and various ways over the last eight years, starting on the day I first visited the Glen Oaks Ranch and met the Sonoma Land Trust’s John McCaull, a diligent champion for this place.

We sat in his kitchen and considered the options, and that’s when he mentioned the Presidio Trust model — a model that has successfully integrated commercial enterprise and housing with preservation of critical open space.

With my collaborators — my Get it Right in My Backyard community (get it, GRIMBY)— I seek solutions. The Presidio Trust model was a solution. Unfortunately, that model fell off the table early, nixed by bureaucrats and politicians.

But it still applies. Scaled down to SDC size, it models a solution. It may be challenging, but building a public-private partnership for this place, remains a possible and hopeful solution.

We stand here today on a campus. A campus is housing and education and enterprise. So let’s consider.

CalFire — bless them forever — wants to relocate and expand its headquarters here in the Sonoma Valley. The campus can accommodate that goal.

The Coastal Conservancy envisions a climate resiliency center. The campus can accommodate that goal.

The community envisions housing that people can afford — people like schoolteachers, medical professionals, public safety professionals, and essential workers. The campus can accommodate that goal.

Open space advocates envision redevelopment that supports a critical wildlife corridor and a vibrant park. A campus with scaled-down, environmentally sensitive redevelopment can accommodate that goal.

The developer envisions a project that will pencil out.

Pencil out. I still have no idea what that means.

But I do know that, in the trust model, everyone gets their pencils out. The designer, the park manager, the homebuilder, the home buyer, the advocate, the politician, the developer — they all get their pencils out.

They take their pencils out in the sunshine, where everyone can see.

They take their pencils out and they run numbers that are real.

They take their pencils out and design a redevelopment enhances lives, not endangers them.

They work together to scale their aspirations to the land.

It’s never too late to take the pencils out. This story isn’t finished. There are letters to write. For the sake of this mountain. For the sake of this place.

Connect with SMP

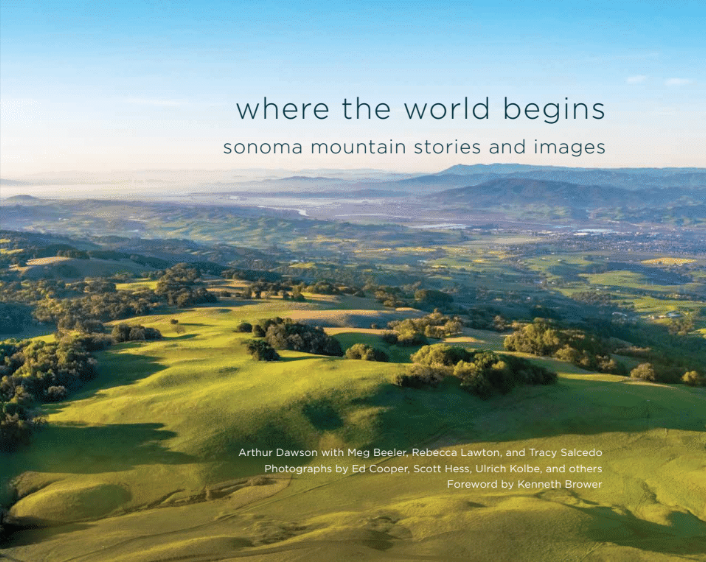

Sonoma Mountain – The Book!

Where the World Begins: Sonoma Mountain Stories and Images draws you into our inspiring natural treasure at the heart of southern Sonoma County. Local Bestseller, IPPY Award 2020. Two purchasing choices below: