Heart full of trails, head full of leave no trace

By Tracy Salcedo

I am an outlaw. A trespasser.

And worse, I’m a repeat offender, in cahoots with other scofflaws like myself. Many of us here in Glen Ellen – heck, throughout Sonoma Valley – are members of a gang that regularly, without malice and pretty much without thinking, trespass on Sonoma Developmental Center (SDC) property. We’ve been doing it for decades.

In our defense, it’s hard to avoid. Formal trails in Sonoma Valley Regional Park and Jack London State Historic Park merge seamlessly onto Eldridge’s web of informal trails. I was introduced to some favorite paths by friends and neighbors; some I just tripped onto while wandering, because… well, I love exploring in the woods. Hence my vocation: hiking guidebook writer. Go figure.

Also in our defense, it’s not like California’s Department of Developmental Services (DDS) has been overzealous about enforcing its no trespassing rule – to its credit. The people working for DDS understood that the open spaces so critical to the health of SDC residents were also critical to the health of their neighbors. There was a posse for a time, comprised of good-hearted, civic-minded folk who asked walkers to put their dogs back on leashes and kids to stay out of the reservoirs (fishing and swimming are also prohibited). But as activity at SDC waned, the posse disappeared. Without those gentle reminders (and the threat of citation), dogs have come off their leashes, and some swimmers and anglers have as well.

Here’s my conundrum: As a guidebook writer and a passionate outdoorswoman, I’m pretty religious about doing right by the wildlands I love. I only write about legal trails, because I have seen firsthand the damage wrought by social trails – the informal paths people carve into landscapes because they want to take a shortcut. I don’t litter. I pick up other people’s litter. I don’t collect artifacts from the places I go. I don’t walk or ride on mucky trails after rainstorms. So I have a hard time reconciling the notion that I’ve been trespassing in Eldridge for the past twenty-plus years. I also understand why the recent letter from California’s Department of General Services (DGS) caused such consternation and confusion.

That said, I also get DGS’s motivations: reducing liability, keeping people safe, ensuring protection of the property’s natural and man-made resources. The huge question of which trails are, and should remain, open around Lake Suttonfield and Fern Lake must be negotiated with the understanding that both access and the wildlands can be wisely and properly conserved. This will take time.

But I can do something, right now, to help. I’ve incorporated boilerplate language in each of my guides designed to help all trail users do right by the open spaces they love, like Eldridge. Because it’s not just about accessibility. It’s also about place.

These guidelines are born of a simple philosophy: Leave no trace. You can visit www.LNT.org for more information, but here are the basics:

Pack out all your own trash, including biodegradable items like orange peels. Take it a step further by packing out garbage left by less-considerate hikers. Stuff it in a pocket, in your pack, in your hiking partner’s pack. Litter has no place in open space.

Protect wildlife, your pet’s life, and fellow trail users by keeping dogs on leash at all times. Take responsibility for your dog’s behavior. And remember, your dog’s poop is not welcome anywhere, so pick it up and carry it out.

Leave wildflowers, rocks, antlers, feathers, and other treasures where you find them. Removing these items degrades natural values and takes away from the next explorer’s experience.

Remain on established routes to avoid damaging soils, tiny creatures, and flora. This is also a good rule of thumb for avoiding poison oak and stinging nettle, common regional trailside irritants.

Don’t cut switchbacks; this promotes erosion and creates ugly scars on the landscape.

Sound travels easily in the backcountry, especially across water, so avoid making loud noises. Make sure your cell phone is on mute, and use it only in case of emergency. If you must listen to music, conduct business, or help solve your best friend’s romantic issues while on the trail, speak softly and use ear buds, not the speaker function.

Many trails are multiuse, which means you’ll share them with other hikers, trail runners, mountain bikers, and equestrians. Generally, hikers yield to equestrians, and mountain bikers yield to all trail users. If you are hiking in a group and encounter other hikers on a narrow trail, whether passing or coming in the opposite direction, proceed in single file. Generally, the uphill hiker has the right-of-way. But common sense should prevail in all trail user encounters. Talk to each other, and share responsibly.

Use outhouses at trailheads. If nature calls while you’re on the trail, pack your poop and your toilet paper out like you would pack out your dog’s waste. You can also carry a lightweight trowel to bury human waste 6–8 inches deep and at least 200 feet from any water source.

Don’t approach or feed any wild creatures. Honestly, they are avoiding you. That cute squirrel eyeing your snack food is best able to survive if it sticks to acorns. The rattlesnake knows you’re too big to waste its venom on; heed its warning, keep your distance, and it won’t bite. The mountain lion has tastier things to eat, so should you meet one on the trail, talk to it, make yourself bigger, and back away slowly. Running makes you look like prey.

If we leave no trace, we do no harm. On any trail, permitted or not, we have the power and obligation to set the example. Perhaps others will follow, and maybe, eventually, no one will leave a trace. We may be trespassers on Eldridge’s trails (for the time being), but instead of a gang of scofflaws, we can be a gang of stewards.

Connect with SMP

Sonoma Mountain – The Book!

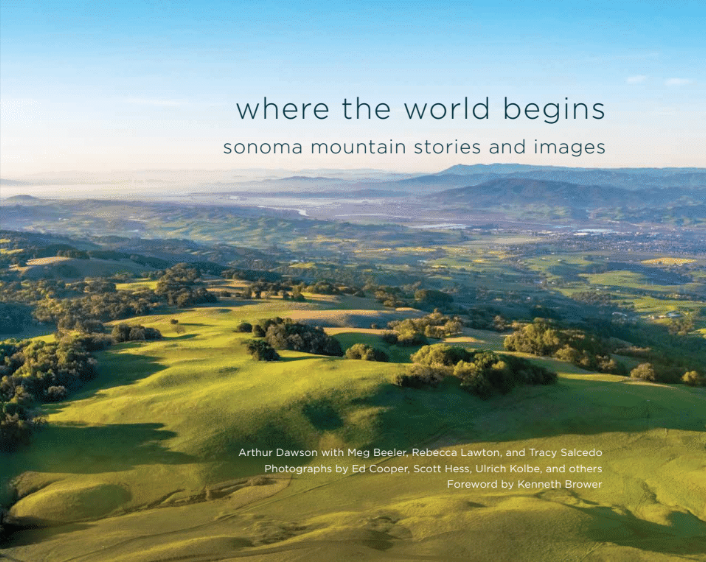

Where the World Begins: Sonoma Mountain Stories and Images draws you into our inspiring natural treasure at the heart of southern Sonoma County. Local Bestseller, IPPY Award 2020. Two purchasing choices below: